Why Me?

Module 1: Why Me?

Why pharmacy staff?

Pharmacists are the most accessible health professionals in the United States.7 With training, pharmacy staff can serve as gatekeepers who recognize suicide warning signs and refer individuals for assistance before they attempt suicide.1-6

Pharmacists are well acquainted with suicide—or the threat of suicide—in their practices:

- A study in North Carolina found that 1 in 5 community pharmacy staff had been asked to advise on a fatal dose of medication.

- 22% of pharmacy staff had patients request a lethal dose of medication.7

- 22% of pharmacy staff know a patient who has died by suicide.7

- Suicide can be prevented.1

- Pharmacy organizations agree. In 2019:

- The American Society for Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) board stated that suicide prevention is a pharmacist’s role.

- The Joint Commission recognized the role of pharmacists in suicide prevention.

Medications and suicide

More than 140 medications are labeled for risk of suicide or have a potential for suicidal behavior. Several medications labeled for potential suicide risk are in the top 200 for highest dispensed volume. These medications include the entire class of antiepileptics, drugs used to treat urinary incontinence, smoking cessation agents, and an antibiotic.8

More than 140 medications are labeled for risk of suicide or have a potential for suicidal behavior. Several medications labeled for potential suicide risk are in the top 200 for highest dispensed volume. These medications include the entire class of antiepileptics, drugs used to treat urinary incontinence, smoking cessation agents, and an antibiotic.8

In 2019, 30% of all suicides were carried out by poisoning, which included prescription overdose drug deaths.9

Suicide in the United States

- Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States.11

- On average, there are 132 suicides per day.11

- Men die by suicide 3.6x more often than women.11

- Veterans are 2x more likely to die by suicide than non-veterans.12

- 74% of medical office visits end with a prescription, meaning that many patients who are at risk of suicide visit pharmacies to pick up their prescriptions before their deaths.13

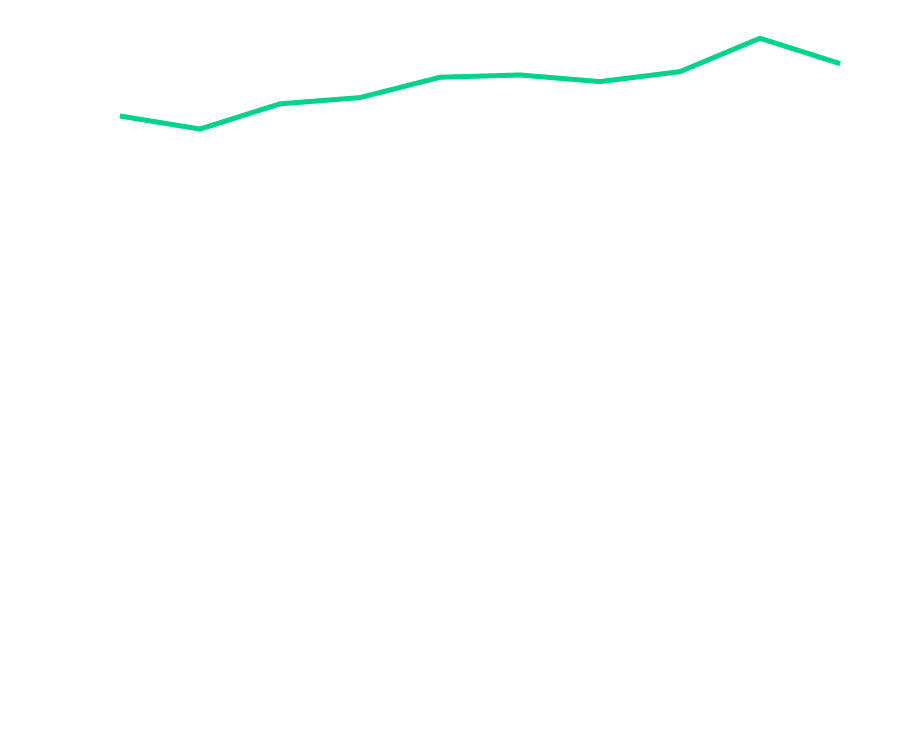

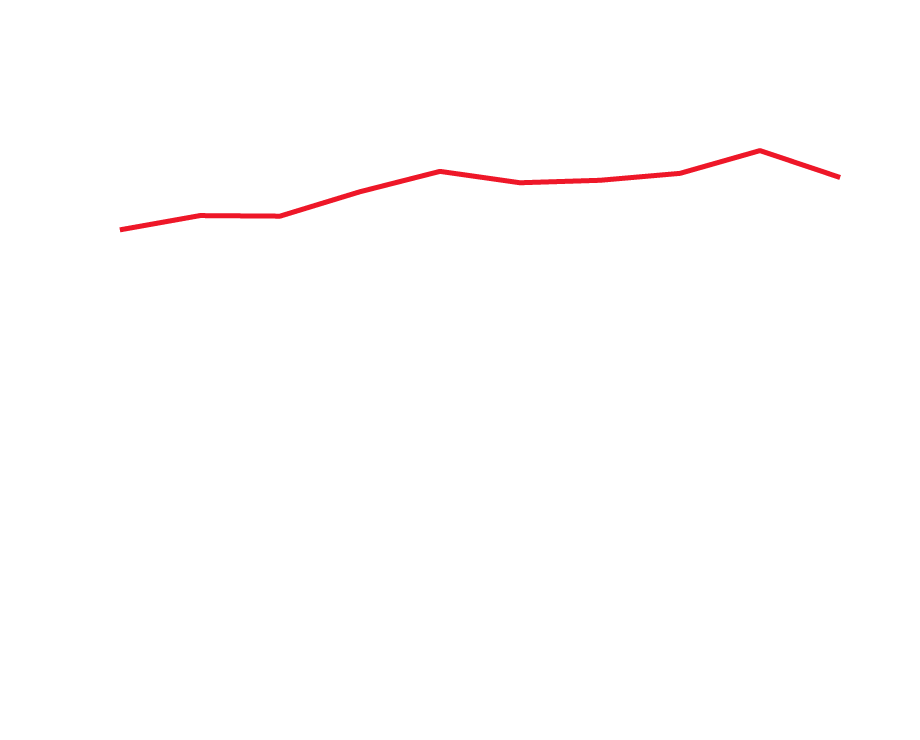

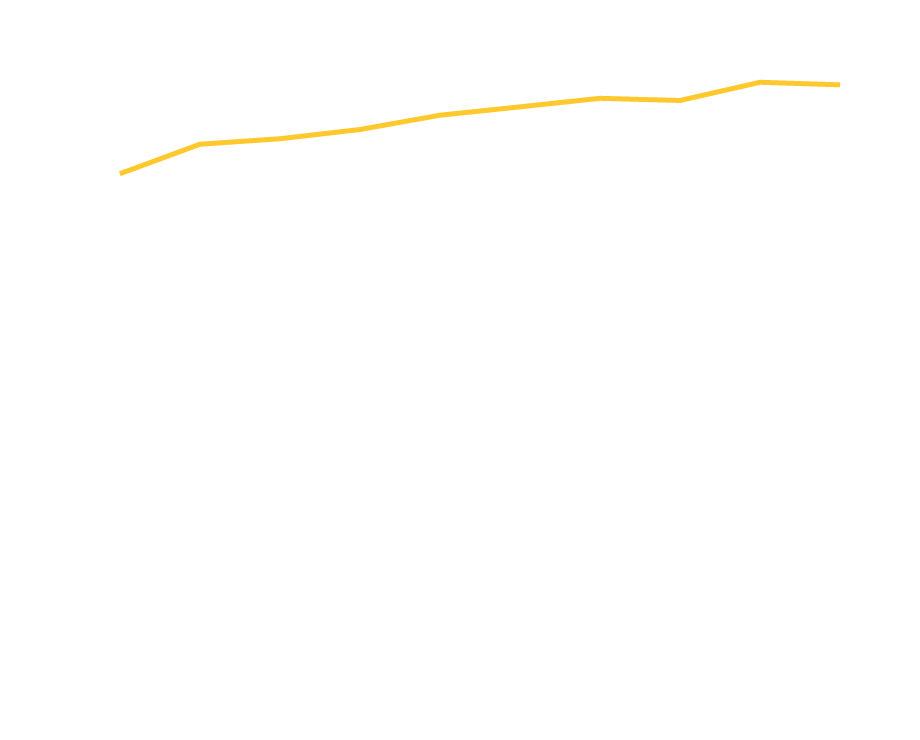

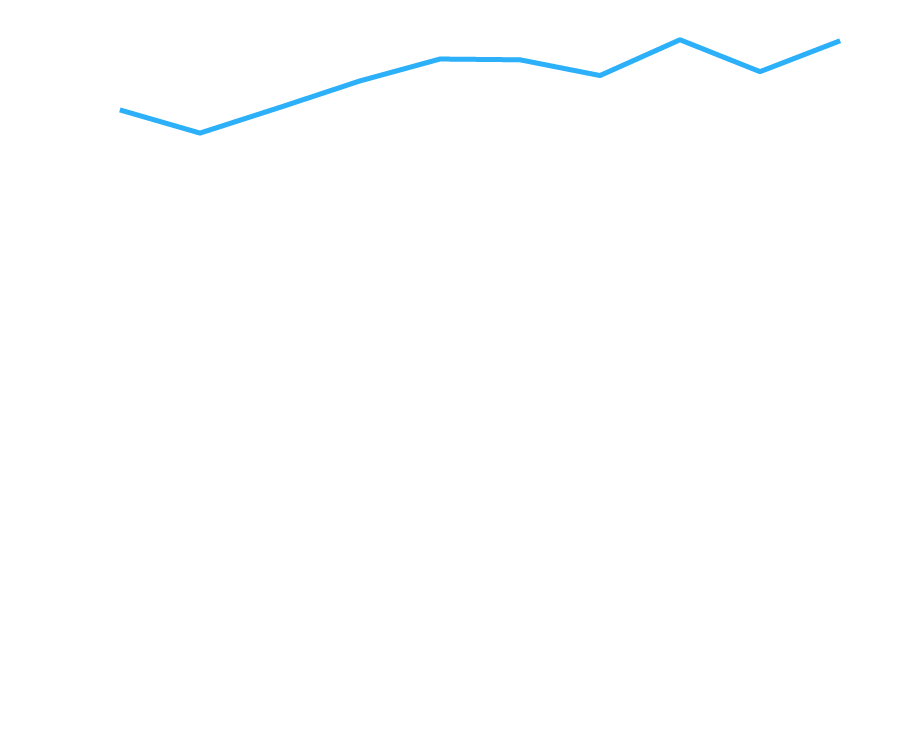

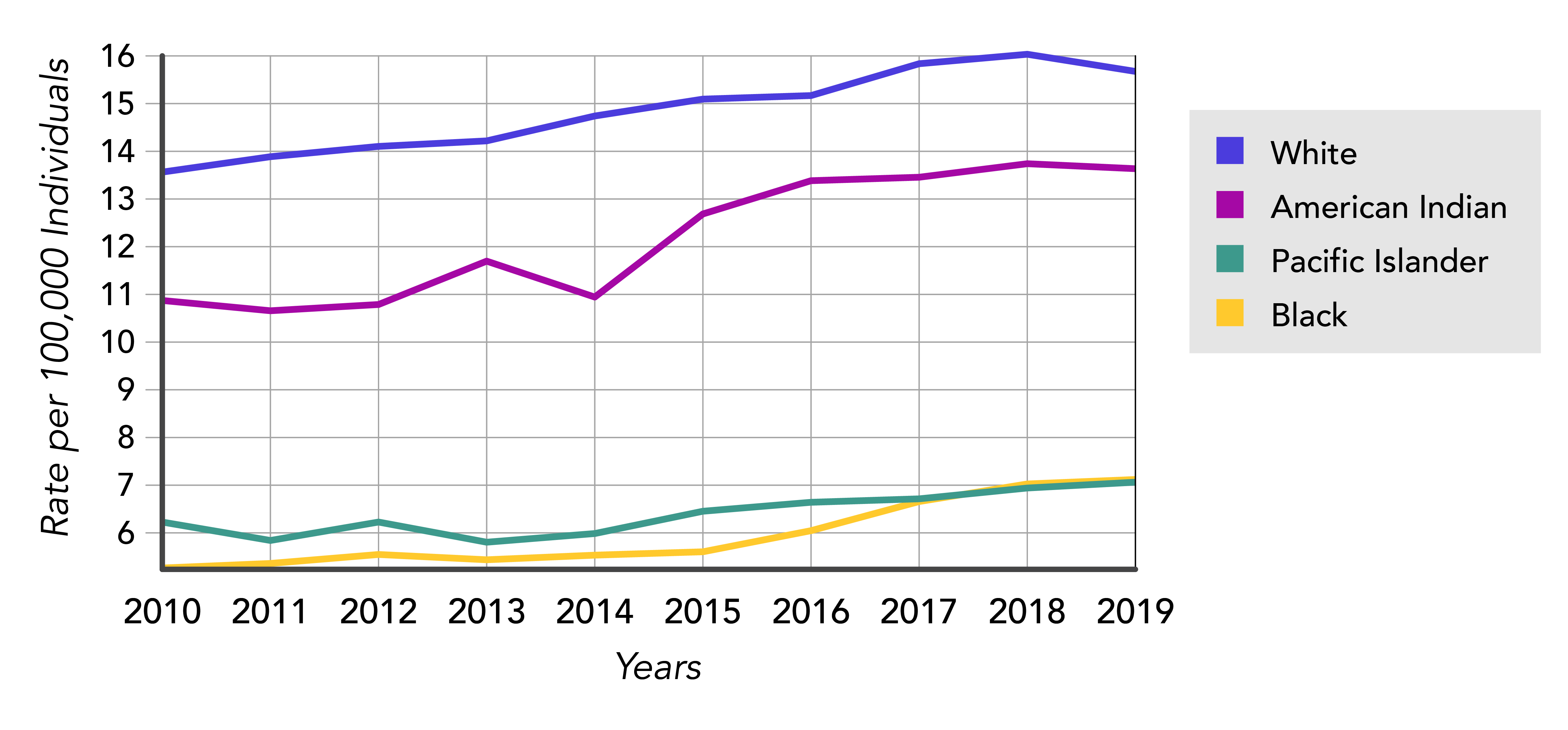

In 2019, the highest U.S. age-adjusted suicide rate was among White Americans (15.67). The second-highest suicide rate among American Indians and Alaska Natives (13.64). Lower rates were observed among Black or African Americans (7.04) and Asians/Pacific Islanders (7.04). Please note that the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) records Hispanic origin separately from the primary racial or ethnic groups of White, Black, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and Asian or Pacific Islander, because individuals in all groups may also be Hispanic. For 2019, the overall rate across groups of suicide for non-Hispanics was 15.23, and for Hispanics the rate was 7.24.11

The highest rate of suicide is among adults who are 45 to 54 years old. Click the other ages (listed to the right of the graph) to compare rates among the entire population.

Want to learn more? Visit the following:

| Resource | Website |

|---|---|

| American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) | https://afsp.org/ |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Suicide Prevention |

https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/ |

| Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC) | https://www.sprc.org/ |

| Veterans Crisis Line | https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/ |